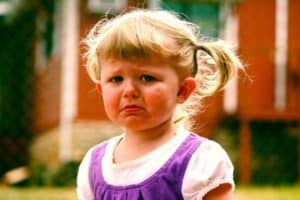

The Hardest Lesson – The Power of “No”

Teach your children that “No” means No”

God uses the word “no” a lot with me. I still don’t like it, but I am a lot more accepting of His sovereignty now after many years of life and many, many observations that “no” was really the best answer after all. However, parents have two problems: they aren’t God, and many children don’t learn “no” without a fight; after all, yes is so much more fun.

This lesson goes hand-in-hand with patience. See Part 5 of this series of articles, The Power of Patience. But there is a finality in “no” that is so much harsher than “not yet” or “maybe later.

There are a number of challenges with “no.” One is that you may feel that you have to explain why “no” is the answer. You might, but not always. There are times when “No and I said so” is the final answer and nothing more needs to be said. No, you aren’t God, but you have an element of human sovereignty over the household, or at least over your child.

“No” with an explanation can easily turn into an argument or a negotiation. Those are hard to win and the tougher the argument or negotiation, the more likely you are to give in. The end result of your being flexible is that your child learns to manipulate you. More and more arguments and negotiations will ensue. You will have succeeded in teaching your child something, but not something good.

Here is an example for illustration. Your 7-year-old child wants a cell phone. You are fully aware of the risks: scam callers, predators, and internet access issues. You are also aware that blockers and other software to protect your child are far from perfect. Your answer can be:

“No.”

“Not yet.”

“Maybe next year.” However, know that your child did not hear “maybe” and understood what you said as a promise for next year.

“No. You don’t need it, and I don’t think they’re appropriate for a child your age.”

“No, a phone would interfere with family time and schoolwork.”

Which answer you choose will depend upon multiple factors including your finances, your relationship with your child, your child’s age, your child’s maturity, the surrounding environment, whether family time is a real factor, and more, possibly including even the way you are asked for a phone. You have to answer the hard question that your child did not ask, and that is what is best for your child and your family right now. A cell phone is perhaps not a good example because there is no middle ground. If possible, offer an alternative that may soften the “no” to what was really wanted. Just be careful not to encourage endless negotiation.

Let’s try another example to test the boundaries of this. Perhaps when your child is young, you set a rule of the TV being off at 7 pm and lights out and into bed at 8. It is reasonable that as your child grows older and hopefully more mature, that you can make the times later. Of course, it is still possible for the times to be unreasonably early in your child’s mind because, “Jimmy gets to stay up a lot later.” The reality is that growing children need more sleep than they realize, the glare of electronics is bad for sleep, and who knows what time Jimmy really has to go to bed. Those are arguments/explanations you can use but that may not work well at all, at least not for long.

Rather than remain inflexible, be flexible. Watch your child. You will see signs when the inevitable request is coming. If you catch those signs, offer a later time before the request is made. If s/he makes the request, say that you were thinking of extending it, but instead of 9:00, let’s try 8:30.

At one time a child psychologist was asked by a parent for the best age to start putting good boundaries on her child’s behavior. The psychologist asked her child’s age. The mom said five. The short answer was, “At least five years ago!”

Start the limits early. And remember Part 5 on patience? You need to prepare yourself for the claims of “That’s not fair.” Avoid my favorite sarcastic response to that claim, “Sorry, the fair is in February at the Florida State Fairgrounds.”

The disciplinary idea of “time out” is a good one. Children get stimulated easily and their arguments become impassioned quickly. They do not have the experience of seeing other viewpoints and they think what they know is right. Their world is a lot more black and white than ours with far, far fewer shades of grey. Tell them to take a five minute or even ten-minute break. This does several things, one of which is allow them child to calm down. The other is that it also allows you to calm down.

It may come down to the simple statement, “This discussion is over, my decision is final.” You may have to enforce that by turning and walking away. But remember that you may need to enter back into a calm discussion an hour or two later, explain your reasoning and say that the decision can perhaps be revisited in a month or two (or whatever time frame is most appropriate). For a few ideas on what to explain and how to explain “no,” see Psychology Today, When and How to Say No To Kids. As might be expected, the ideas are secular, but the last allows some spiritual application, “Say No When It’s Against your Values.” I would rephrase that to “Say No When God Says No.”

There is an important lesson in this and other parts of this series of articles; your child has learned and is learning from your own behavior. How well do you take “no” for an answer? Do you argue where you can be heard? It is amazing what children hear. When I was about ten, my father said a known bad word in the car because of another driver’s dangerous driving. I already knew that word, but a few minutes later my 4-year-old half-sister who was in the car blurted out the same word. She was promptly disciplined and my father said, “I don’t know where she learned that word.” His use of that four-letter word was so casual, he didn’t even realize he had said it – or that he had taught her to say it. Children are watching and learning, even when you don’t realize it. See Part 2 of this series of articles for a great video illustration of this point.

Regaining Lost Ground

But it is quite possible you have already passed the stage of “no” and have entered the world of arguing, negotiating, and manipulating and, unfortunately, you are losing. Here are a few ideas for regaining the high ground.

Script your comments and position in advance

You know your child well enough to have a pretty good idea of the arguments that will be made, the approach(es) taken, and the inevitable ugly turns that may have defeated you in the past. Role play the next argument in your mind or even with a friend. Discuss and consider possible approaches and responses. This is important because your child thinks you are going to give in, and new resistance will be unacceptable. Preparation is essential. I did it for over 40 years as a trial lawyer and found that rehearsing many times usually resulted in my being far more prepared and better able to withstand the opposing arguments. Preparation will also help you keep your own blood pressure down and you will get less angry. Angry arguments tend to get loud and loud arguments are teaching something you don’t want your child to learn – volume works! No, it doesn’t.

You might even want to write some of the arguments down. Just be sure the computer file is securely password protected or the notes hidden very well. You may even be able to use some of the written thoughts because often the appeals come by text.

What you say and how you say it is especially important in the area of threatened punishment. Children learn quickly when you bluff. They often don’t take a change in your courage well. Don’t threaten punishment that you won’t or can’t enforce. Make it meaningful, but not excessive. “You are grounded for a year” or “if you do that, you are out of this house” are probably not realistic and may not be the most helpful in the long run. Punishment is to promote a better relationship in the long run, not to permanently damage it. Of course, there are moral limits and some lines cannot be crossed, but draw those lines carefully and only with prayer and careful thought.

Start with an easy one

You have to start standing firm somewhere. Make it an issue where you know you are right, where there are few, if any, good counterarguments, where the results will not be too harsh, or where you can easily explain your position. One natural thought, probably the worst one, is to start saying “no” to almost everything. You are looking to teach discipline, not rebellion.

Regaining authority over a strong-willed child who has been winning over you is a long-term proposition. It will take patience, planning and careful thought. The essential element you are looking for is your consistency in enforcing your decision. Start with an easy one, stand firm, and then gradually add a bit more control and a few more limitations. Remember your goal. A child who hears “no” and accepts your leadership.

Another way is perilously close to negotiating, but may be necessary if you have been consistently losing. This does take scripting and planning and a high level of anticipation about the upcoming request, but it can be effective. Offer limited options and have your child choose. “I want the car tonight” may be answered by “Only if you have your homework done before you go and if you are back by 10 pm.” Your child has a choice, and can say “yes” or “no.”

One caution! Do not allow your child to play one parent against the other. You need to be on the same page and even on the same line on these issues. There may be times you have to say “no” or “yes” to keep family peace. These are times for a prayer, a quiet discussion, and family accord on future decisions.

Always keep your eye on the real goal, a child well-raised who knows Jesus as his or her Savior (Proverbs 22:6), and who has the discipline to say “yes” when it is right, “no” when it is right, and the wisdom to be able to choose well because you were a Godly parent.

About the Author

John Campbell has retired from a 40-year legal practice as a trial attorney in Tampa. He has served in multiple volunteer roles at Idlewild Baptist Church in Lutz, Florida, where he met Jesus. He began serving as the Executive Director of the Idlewild Foundation in 2016. He has been married to the love of his life, Mona Puckett Campbell, since 1972.